A Conversation : by Debayudh Chatterjee

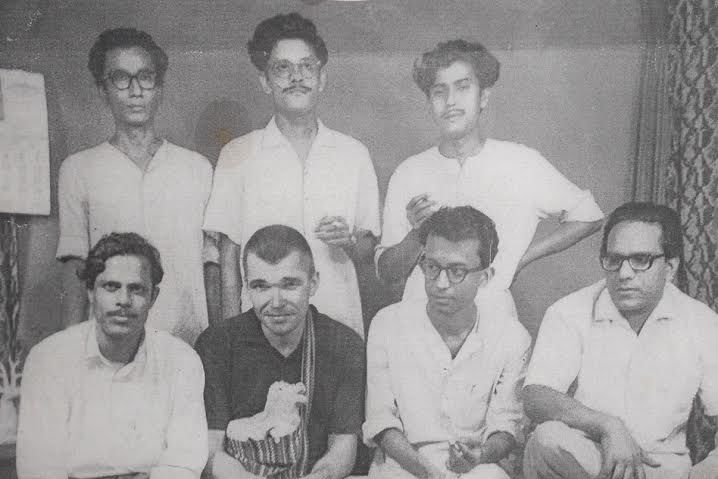

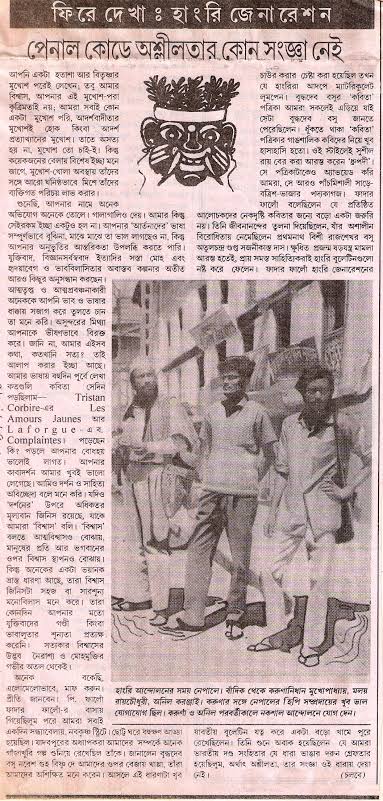

Debi Roy was born in 1938 as Haradhon Dhara to an impoverished under-caste household residing in a slum in Howrah. He had to discard his real name to survive in a literary establishment dominated and hegemonized by the upper-class elite. Roy was one of the four founder members of the Hungryalist movement. He was hailed to be the editor of the first manifesto of the movement that came out from Patna in 1961. His slum address was used for official correspondence during the movement. Pitching an under-caste in the forefront was conscious effort to lodge an attack on the Brahminical arena of Bengali poetry. Roy passed his school final in 1958 and IA in 1960 before enrolling himself in a course on library science at the University of Calcutta. His first anthology Kolkata o Ami (Kolkata and I) came out in 1965. He was arrested later on the ground of obscenity along with other members of the Hungry generation. While he was suspended from his government job, the lower court soon acquitted him. After 1965, as the movement fizzed out and splintered into different groups, Roy continued writing as an individual in his own merit. Till date, he has authored more than ten titles in poetry, translated extensively from Hindi into Bengali, and wrote three books of non-fictional prose.

Debayudh: Let me begin by asking why you changed your name to Debi Roy.

Debi Roy: There wasn’t any other way apart from adopting that name. No way whatsoever. There was so much of Brahminism around me, so much of humiliation… When they cannot topple over you in any other way, they seek resort in caste. This is just a way of suppressing you. Some of my own friends can be accused for that crime. Some very close friends who used to frequent my slum once upon a time. They came at an hour when my mother couldn’t eat… But they were ones to humiliate me first. They still do it… even now… though their powers have ceased to exist.

Debayudh: What I know about the movement is that after four years of its inception, it got fragmented. Some of the members denied their allegiance in the court, some pioneers changed their stance, a lot of other nasty things happened. You were one of those who actually faced the music. You were arrested, heckled, suspended from your job… Today, after more than fifty years, on retrospect, would you relate that as subtle form of caste oppression?

Debi Roy: I despise caste. I have no words to condemn what happened to me. It’s just that I have to remain silent. My wife passed away last June, on 24th… I am not in the right state now. I am a self-made man. I was born in a slum and now I live in an apartment with an air-conditioner in each room. I never imagined I could climb such heights.

Debayudh: Did you ever write directly on caste?

Debi Roy: Nirendranath Chakrabarty once told me that I can skillfully enmesh my life in my poetry. He once asked me why I don’t write an autobiography. I mocked back, should I write a Jibansmriti? Tagore wasn’t any less humiliated for being a Brahmno… a fallen Brahmin… But why would I write? Who would be interested to read about me?

Debayudh: I can share an anecdote with you. In 1926, Tagore attended a Namasudra conference in Dhaka. He was severely chastised by his folks at Viswabharati. He never went back to Dhaka again, that was his final visit. AK Biswas has written about it in detail.

Debi Roy: Imagine. Such is the consequence of the caste system. But Bangladesh has been very hospitable to me. I have been there four times as of now. However, Tagore is zillion times greater than me. I owe my life to him.

Debayudh: Although Tagore was preoccupied with discrimination throughout his life, he kept altering his views on the caste system. You can track that change from Gora to Home and the World to a couple of short stories to Chandalika. He preferred Gandhi over Ambedkar at the time of the Poona Pact. I find it deeply problematic.

Debi Roy: Tagore championed the supremacy of the human spirit over anything else. He was in and out a humanist. There’s one thing that I can tell you. If you leave everything aside, the profound knowledge and love that the Geetabitan speaks of transcends any barrier imposed on humankind. Apart from the Ramkrishna Kathamrita, one book that keeps me alive and immensely influences me is the Geetabitan. Sri Ramkrishnadev didn’t have a single degree, but the kind of wisdom that runs through his words is amazing. Even Tagore didn’t have a university degree. But look at how these two men went on to shape the consciousness of the entire civilization.

Debayudh: Yes, Sri Ramkrishnadev and, later on, Vivekananda, did play an important role in reforming Hinduism from within. They were strictly against caste discrimination albeit they never thought of annihilating it by its roots. I see a photograph of Vivekananda hanging on your walls. What’s his impact on your life?

Debi Roy: My wife and I have been baptized by the Ramkrishna Mission. We were going through a restless period, a lot of agony and pain. I subscribed to Udbodhon, their mouthpiece, and started reading the Kathamrita. I realized it was already too late, no point in delaying further, we decided to embrace the Mission.

Debayudh: This leads me to my next question. If you think it’s too personal and uncomfortable, do refrain from answering. The Hungry Generation began by repudiating the existence of God. I remember that you wrote in one of your poems, “It’s more important for me to look for bread than run after an unnecessary God…”

Debi Roy: That was solely Malay’s idea. Most of it was gimmick. Not mine. Whatever came from my side was youthful folly.

Debayudh: Describe the initial years how you met Roychoudhury brothers, Shakti Chattopadhya, Subimal Basak in those early days of the movement. What it was like to be part of it?

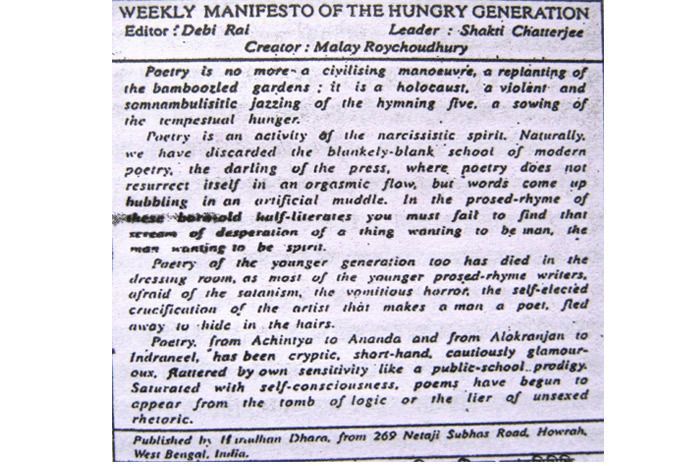

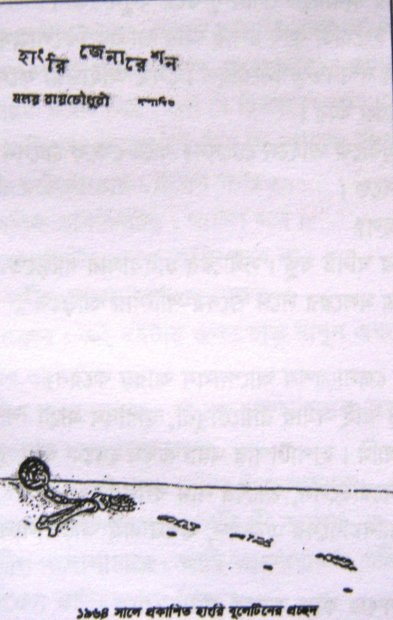

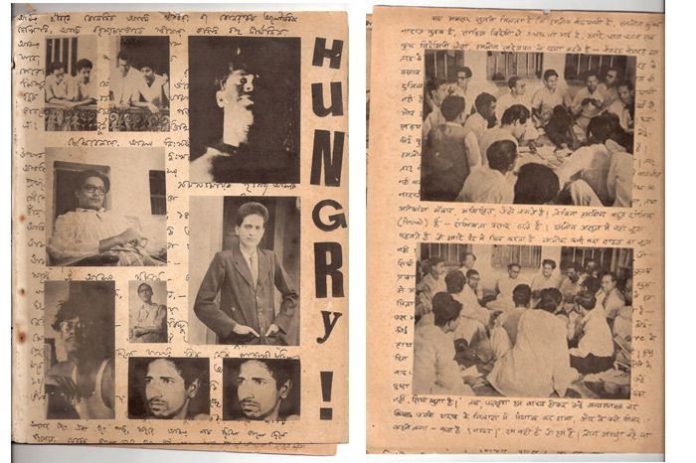

Debi Roy: The “Hungry Generation” was mostly conceived by Malay. He was the one who wrote to me. Later on we met face to face in Subarno Upadhyay’s rented apartment. Subsequently I was introduced to the other members of the movement. In 1962, in the month of April, Malay brought out the first Hungryalist bulletin and mailed it to me. It was published in English. Creator: Malay Roychoudhury, Leader: Shakti Chattopadhyay, Editor: Debi Ray. It’s natural to protest against convention, social evils, and injustice when you’re young, quite natural to be a non-conformist. Someone who accepts everything is a person who cannot question. That’s certainly not the trait of youth.

Debayudh: Could you help us understand the Hungry aesthetic better?

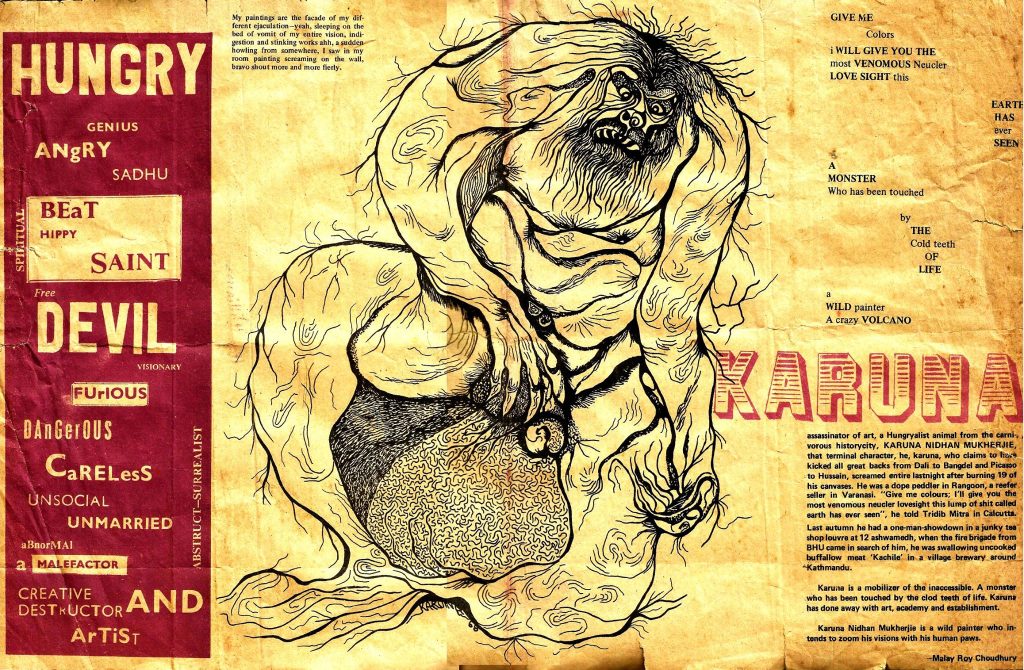

Debi Roy: Immersed in youthful folly, the Hungry Generation dared to challenge the norms and ethics with whatever cultural capital it had. The movement opened up a lot of windows in our minds. There was no hesitation, but pride. I used to read a lot, at times, a lot of random stuff at that age. John Keats made me thinking, “Thou was not born for death, immortal Bird! No hungry generation tread thee down…” Malay told me how he was influenced by the English poet Chaucer’s phrase, “In sowre hungry tyme”. Spenglar’s theory of cultural degradation provided the philosophical axis of the Hungry generation. Uttam Das researched on the theoretical and philosophical implications of the movement.

Debayudh: Can the hungry aesthetic of breaking the state of art exist without the classical dictum?

Debi Roy: Poetry or literature in general, is not a boxing ring that you need to knock somebody out to gain fame. I write by myself, for myself. Alone. Surrounded by stalwarts on all sides, I live a low-profile life. I do not have any sense of inferiority because of that. I ask myself, am I educated? I have never been educated in the institutional sense. I did not have the opportunity to. I prefer not to overload my writings with postmodernism and other theoretical back-scratching. My liaison with poetry is like my long conjugal life. I am still enamoured in her spell. I will be until I die. Is there an end to knowing one’s self? There is a need to bridge the gap between life and death. That is why you need poetry. It’s another name of delving deep into life. I have to leave this world someday even if I don’t want to. Death is inevitable, life ephemeral. But that does tamper with its charm? I find these ideas of ‘classic’ and ‘eternal’ quite problematic though. My real work is with poetry.

Debayudh: Do you think the Beats and the Hungry generation had anything in common and if they have inspired each other? Tell us about your interactions with the Beat poets and publishers.

Debi Roy: When the first bulletin came out, I went to the editorial office of Janasebak to hand a copy over to Sunil Gangopadhyay. He quickly went through it once and remarked, “So you’re bringing out all this?” Later on we got to know that he believed that our movement was completely influenced by Allen Ginsberg and the Beats. The Beats and the Hungryalists were similar only on the grounds of being anti-establishment. But one stemmed from the soil of a wealthy nation while another thrived in the dust of poverty.

Debayudh: The leftists often view the movement as a middle class reaction that celebrates urban alienation and male sexual frustration. They accuse that the movement was politically wrong. They say you bring in a new order of morality while trying to tackle the classical Bengali bhodrotta with obscenity and rage of alienation. What is your opinion on that?

Debi Roy: I’m not into politics. That’s not my cup of tea. Why don’t political leaders across party lines teach us to love people irrespective of differences? Aren’t the ones in opposition human beings too? Some of them travel enveloped in security, in bulletproof cars, instigate the common mass from a distance, and go back to their ivory towers. There are exceptions that must be respected. But why are there so many commandos around the leader of an impoverished backward country? Why can’t the peasants avail the irrigation and manure they deserve? Why do the workers out of work stare depressingly at the gates of factories that have been shut down? Why do trade unions end up being centres of other profitable trades? Why are the youth still unemployed? Why are they forced to choose such despicable ways of life? But, in the middle of all this, I know of a communist leader who refused to take more than a piece of fish on his platter. There was another who did his own laundry. You cannot imagine such a brand of politics in our times.

Debayudh: Tell me more about your engagement with the Hungry Generation.

Debi Roy: There are a lot of memories. Some of them are too sad to recount. I remember spending a month in Varanasi on a friend’s travel pass. Probably we hardly had any inhibition those days. I adjusted quite well in the household of a widow and her son. That’s where I met Anil Karanjai and Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay. Once, after I wrote a piece on Subhash Ghosh, an Englishman, probably British rang me and asked whether I speak English. I replied that I obviously do, but I cannot speak in your accent. This is not my mother tongue. I am a poet from Bengal, I write in Bengali. I am quite satisfied with myself.

Debayudh: Yes, English for most of us is an acquired language. We had to learn it from scratch. It’s obvious that our English will be different from her native speakers.

Debi Roy: We are rather compelled to learn it to make a living. Not that I put much of my heart in it. Like Hindi, I had to master it to find a job. It had nothing to do with my love for that language.

Debayudh: I can understand. I didn’t know a word of Hindi when I first came to Delhi. I had to acquire it.

Debi Roy: Exactly. My bosses thought that they would put me into trouble by asking me to learn Hindi. But it became a boon in disguise. The lady who taught us Hindi came to know that I was a poet who tries to translate once a while. She advised me to take Pragya, the highest qualifying examination in that language, to find a better job. The College Street kept calling me, but why would I go?

Debayudh: That echoes a famous poem by Shakti Chattopadhyay, your once upon a time comrade.

Debi Roy: I have written about it in length. Despite Malay keeps bitching about him, I believe that he was a great poet: a poet in the truest sense of the term. There can be no qualms about it. I have not come across many who had so much dedication for poetry. The rest of the poets I know taught at different places, worked in myriad offices, but Shakti, he gambled his life for the sake of poetry.

Debayudh: I read that he moved out for personal reasons. Once of his affairs didn’t work out and that placed him against the Roychoudhury-s. Shakti Chattopadhyay, as I believe, was eccentric and mercurial to the core. May be that’s something that defines his poetry.

Debi Roy: Very true.

Debayudh: Could you please run us through a timeline of major events that led to Shakti’s parting ways with the movement, and the various fractures within the group until the arrest of the poets when the movement ended?

Debi Roy: One of the reasons is what you said. Shakti fell for one of Malay’s relatives. Apart from that there were personal clashes between Malay and Shakti. Shakti was also offered a job. But, at the end of the day, I believe he is great poet with a timeless appeal.

Debayudh: Describe the last days of your time with Hungry generation. How was it to live with the threat of arrest and other threats that you all faced during the last phase.

Debi Roy: I was suspended for a year from my job—I was working at the head post office in Burdwan then—for being involved in the Hungryalist movement. Some custodians of Bengali literature weren’t happy with us. I was arrested and put behind bars. I was acquitted at last after a lot of storm. My friend Samir Ray arranged for my bail. Our friendship is still intact. During the trials, Gourkishore Ghosh, Jyotirmoy Dutta, and Sunil Gangopadhyay among others stood by us. By then, the famous Times magazine brought us into limelight. Almost all the major magazines and newspapers across the nation started publishing gossips and news about us. Dharamveer Bharti, Khushwant Singh, Pupul Jayakar, all of them came out in our support, collected funds for us, and moved strings to secure our freedom. Pranab Kumar Sen, who was the police commissioner of Kolkata back then, also admitted later on that arresting the Hungryalists was wrong.

Debayudh: Let me get back to the sixties again. The time in which you took up writing was just a few years after Babasaheb Ambedkar’s death. Jogendranath Mondal was back in India and was trying to consolidate his political career. He failed though…

Debi Roy: Hasn’t Debesh Roy written a novel on him?

Debayudh: Yes, Barishal-er Jogen Mandal [Jogen Mandal of Barishal]. It got published from Dey’s. Anyway, it was that time, in the sixties, when you were forced to adopt a different name. I completely empathize with that. But weren’t you even drawn to their anti-caste ideologies? Didn’t they inspire you to fight back? What’s your take on Ambedkar?

Debi Roy: I immensely respect them. The kind of struggle they put up against this system gave voice to thousands who were silenced for centuries. But I got to know of them much later in my life. At that time, in the sixties, I was hardly familiar with their names. I was far from being exposed to their life and works.

Debayudh: I can understand. The middle class intelligentsia of Bengal after partition has always been very hostile to identity politics. As I just told you, Jogen Mandal fought a lost battle of reinforcing caste politics in the public sphere of West Bengal. With Congress on the one hand, and the Communist Party or the Hindu Mahasabha on the other, all the mainstream political forces tried to bring the scheduled castes into their fold. This was carefully done by appropriating, if not shrouding Ambedkar from the common masses.

Debi Roy: Very true. That’s the reason. May be that’s why we never thought so intricately about caste assertion in our times. There’s another reason. In an impoverished land like ours, livelihood becomes an important matter to take care of. As you know, I come from a very humble origin. In the sixties, at the brim of my youth, I was desperately trying to make ends meet. I began my career by working as an errand boy who delivered water and tea. I wanted to get out of the muck at the any cost. I didn’t have much time to delve into other things. Whatever leisure I had, I devoted it to literature.

Debayudh: Yes, it calls for a bit of privilege to actually engage in activism. Those coming from well-to-do families can think about losing their job and writing, distributing pamphlets for free, buying and sending masks to the pillars of the society. Obviously, none of it is free of cost.

Debi Roy: Hahaha… and I had to face the brunt…

Debayudh: …Even the regular doze of booze, weed, hash and travelling to different places need some amount of financial affluence…

Debi Roy: All of these were gimmicks. Going to crematoriums and getting drunk… pure hoax! All of us have done that, the next generations will also do, there’s nothing wrong in that. But all these are gimmicks. These have no connection whatsoever with literature.

Debayudh: Ginsberg once in an article that marijuana brings about an aesthetic experience that a writer requires…

Debi Roy: I don’t believe in that. Literature has no connection with the use and abuse of substances. You can write without excess. I don’t think Tagore needed any drug to write. But Sarat Chandra was completely different. Michael Madhusudan had a life of excess. It varies from person to person. It’s a matter of individual choice. Besides, it doesn’t mean that all of us have to have a similar lifestyle for belonging to the same movement. You can go to Khalasitola and have a blast together, but writing itself is a solitary exercise.

Debayudh: As I went through a lot of anthologies on the Hungry Generation, I noticed that you have been obnoxiously ignored. Not many of your poems have been included, there’s hardly any write-up on you. Although you were the editor of the first manifesto and your address was used for official correspondence, you have been strangely sidelined in the discussions later on.

Debi Roy: All of it is because of jealousy. I achieved what most of them couldn’t. The Sahitya Academy, the ICCR took interest in my works, translated me, included my poems in their definitive anthologies. It is no wonder a group of ghettoized poets would be envious of me. They thought that I was being sold out to the establishment. I reminded Malay that he was promoted to the post of an officer from a clerk. It is the same process. But, leave it, there’s no point in resurrecting old wounds. Let the sleeping dogs lie as they are. There is no perfect job in the entire world, there’s no fun in humiliating others as well.

Debayudh: Yes, opportunism and back-biting have perennially plagued the Bengali literary establishment. I have seen poets shamelessly advertizing themselves and buttering the ones who matter to go places.

Debi Roy: Oh yes, I have a victim of it. A friend from Germany once asked me why I have made so many enemies. He held a powerful position. He was once asked why he never recommended me. He remarked that supporting me would lead to riots.

Debayudh: Such miserable spinelessness.

Debi Roy: Poets behave like bureaucrats these days. They’re running after publishing their pictures on mainstream dailies, inaugurating stupid programs… There’s no point in talking about them. There was one major poet who changed his jersey and made it big. He was after my life once though couldn’t do much. I pity these people. But his wife was a genuine poet.

Debayudh: Let’s go back in time. You were telling me about your humble origins, the immense hard work you had to put in to materialize your aspirations. In the middle of all this, how did poetry happen?

Debi Roy: There was a library near our place. I went there to while away my time or forget the pangs of hunger. I started reading, I read as much as I could. I still remember the librarian. He used to smirk and enquire whether I had no other work. There was another library near the Howrah Girls’ College. I spent hours there reading authors like Bankim Chandra. Not that I understood all of what I read but I realized that literature is my poison. I also loved music. But once literature takes over someone, his life and afterlife are perpetually destroyed. (laughs)

Debayudh: Did you face any sort of caste discrimination from the other members of the movement or other writers when you started publishing?

Debi Roy: There are things that I don’t want to recollect. So much of shit has been spewed. Shaileswar Ghosh used to think a lot about history. I was perpetually humiliated by him. Sub-altern-heaven-afterlife-soul-moksha-the four varnas- these are his truths. Some of those Hungryalists are doing the Vedas and worshipping now to make a living. Just as Jabali once told Ram, do not be blinded by deceitful Brahmins; only the dumb can pin his faith in spirits, afterlife, rituals, reconciliation, etc, even in post-modernism! Will these theories enable the lower castes and marginalized with two square meals a day? Will the roads be repaired after the elections? Proper drinking water? Will the peasants get irrigation, manure? Education for all? Light? Will the youth from ‘our homes’ get a job? Equal opportunities? Will the wheels of historical oppression come to an end? An end to discrimination? Prejudiced mentalities? Will all problems be solved if a percentage finds employed in software firms? Will the closed factories start producing again? People like me who have fought their way to privilege, do we carry out our duties? Such hullabaloo about caste! That Dalit, that OBC, that Yadav, all that discourse with names. Young progressive people laugh at it. One of them once asked me, is your ‘friend’—he was referring to Malay—from that time, a big fan of Manu? How could you tolerate him since the sixties?

Debayudh: Do you have any regrets?

Debi Roy: Once a friend told me that I made a major mistake in my life. He argued that had I passed my masters, I would have got a far better job and a lot more time to read and write. But people do make mistakes. One’s life is defined by his mistakes. There’s no point regretting them. Another mistake that I made was not to secure a medical insurance. I still haven’t been reimbursed for the heart surgery I had to undergo. This is the condition of a central government officer in an independent nation.

Debayudh: Thank you Debida! That’s all for now. It was beautiful getting to know you.

Debayudh Chatterjee (b 1991) is pursuing his MPhil at the Department of English, University of Delhi. While his dissertation looks at Dalit writing as a ground of contention between caste and class ideologies, he takes active interest in the avant-garde, counterculture, and 20th century Bengali literature. Apart from being employed as a Project Fellow at the department he is affiliated to, Chatterjee is a published poet in Bengali, having three titles to his credit.